Written by Art Petrosemolo

Writing for Lancaster Farming, or Lancaster Newspaper’s weekly papers, I occasionally (well more times than I’d like to admit), accept assignments on subjects I know absolutely nothing about but they seem interesting.

I have done research and a story on historical baking at Landis Valley museum and learned about beehive ovens; I also have done stories on the tobacco and wheat harvests, Amish Marriage Encounter (who’d-a guessed) and Ben Shirk’s East Earl sawmill, among others.

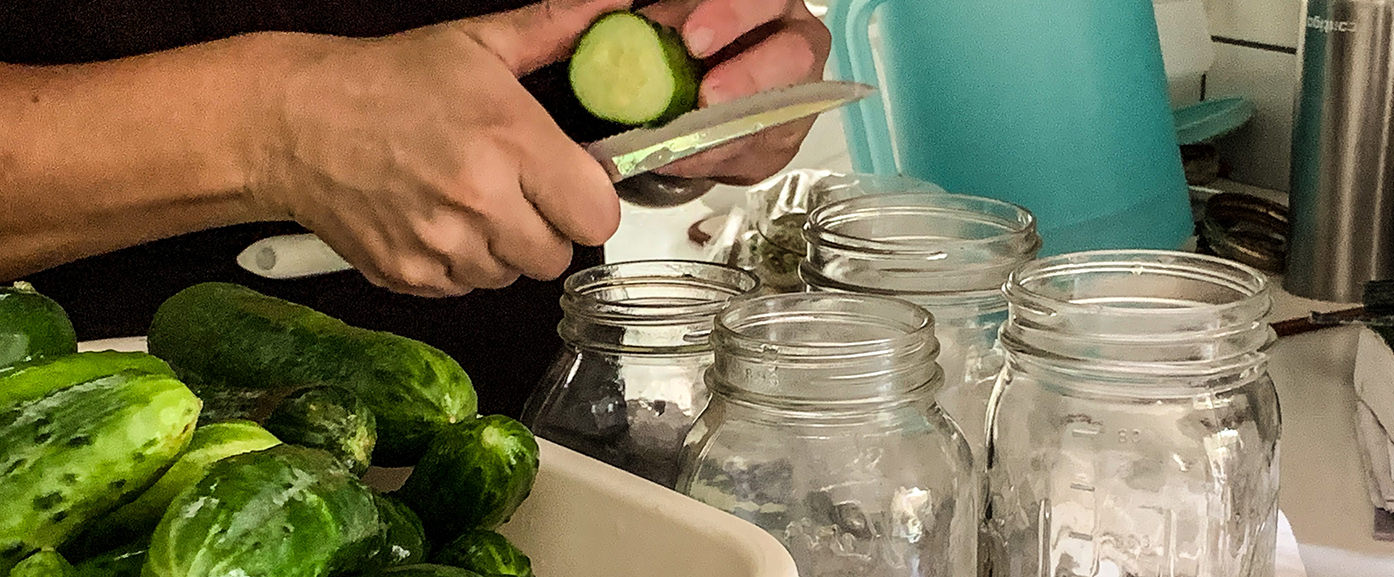

Recently my Lancaster Farming editor said she was looking for a story about a “farm woman.” Well, the topic was pretty nebulous and I was not interested in knocking on farm doors to finding “interesting farm women,” so I asked her to give me an idea of what she might be thinking. Her response was “food preservation” or what we know here in Lancaster County as canning or “putting up” fruits and vegetables.

Again, it was a subject I knew nothing about. I grew up as a city-suburb kid in Southern Connecticut. My mom was a schoolteacher. She didn’t spend the summer canning green beans. The closest I have come to the subject since moving here is accepting canned peaches and strawberry jam from Amish friend Ruth Lapp. My curiosity got the best of me on canning and I said “yes” to the assignment and began my research.

On food and agriculture stories, my first or last call is always to Penn State’s (Lancaster) Extension Service. This time I talked to a woman in food safety and asked her for a tip to include in my story—something like washing your jars thoroughly before using. Instead, she gave me an earful about how serious food preservation is and can be and how important it was to use the right method for each fruit or vegetable depending on the acid content of the food!

Well, immediately, I started thinking about all the canned fruits and vegetables I had eagerly accepted from friends and were they indeed processed safely as my food safety educator had stressed.

Well, the answer was yes. Everyone does things a little differently but most everyone to whom I spoke, did personal or commercial canning and were very conscious of proper safety methods and the dangers of Botulism spores growing in canned foods.

I also learned that most canners use recipes handed down from their mother or grandmother and have never been sick so assume that their relatives knew what they were doing. And in most cases they did.

A little history before I tell you of my canning adventure. Canning, or what probably should be called “jarring,” was invented when a French chef Nicholas Apperta in the 1700s—who suspected that air caused food to deteriorate—experimented packing jars with produce, sealing them with corks and wax and boiling in water. His suspicion was wrong, but his process worked eighty years before another Frenchman, Louis Pasteur, discovered that it was pathogens that grew in food that caused spoilage. Pasteur discovered those pathogens could be destroyed with heat. It was the science behind food preservation and the process still carries his name.

So, back to the present. What I learned fairly quickly from the people I visited and my United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) research is there are three general canning operations used—besides freezing—in food preservation.

Canning is usually is done by cold (now called raw) pack, hot pack and pressure canning. Raw pack canning is done with low acidic vegetables. The raw food is packed into jars and covered with juice or syrup that has been brought to a boil. Then the canning jars are processed per USDA guidelines usually in a pressure canner or boiled in a water bath (after the addition of white vinegar or citric acid to change the PH per scientifically tested recipes).

In hot pack canning, the jars are filled with precooked or partially cooked hot food and liquid prior to processing. Pre-cooking drives some of the air out of the food and allows tighter packing of the jars. In the past some canners used what was called the open kettle method where hot food was put into a jar and sealed without processing. Food preservation scientists, however, no longer recommended this even for pickles and jellies.

Even if you are not clear on the science of food preservation and home canning, following USDA (https://nchfp.uga.edu/publications/publications_usda.html) guidelines, instructions from universities like Penn State Extension or online food websites allows you to be safe and successful in your efforts.

Researching canning, I visited several Plain Community homes and watched moms work with their children to can vegetables. Most used the hot pack canning method although for things like pickles, raw pack seemed to be preferred. However, most Plain Community moms were more than aware of the need to process low acid foods using vinegar or citric acid if they were not pressure canning.

I visited two commercial canning operations close to us here at Garden Spot Village. Fannie Fisher and her husband Ben run Home Grown Cannery on Peters Road in New Holland. They have a small retail operation there and a stand at Green Dragon Farmers’ Market. They have been in operation for eight years and use a hot water canning bath adding vinegar or citric acid as per the scientifically tested recipe when processing low acid vegetables.

It’s the same for Annie’s Kitchen, a pretty big operation in Ronks. Owner Steve Stoltzfus sells canned fruits and vegetables wholesale to farm markets up and down the East Coast and has a compact production facility run efficiently by a small crew of Amish women. They too process both low and high acid foodstuffs without pressure canning, using white cider vinegar as an additive.

The canning story was a hoot for me to research and write and it is due out in an upcoming issue of Lancaster Farming. I feel much more comfortable now accepting canned produce from my friends and I’ll ask in a non-threatening way what canning method they used….. or has it gotten you sick….? (Only kidding on the second question).

I wonder what my next adventure will be?